After doing a little bit of game development I’m convinced good game dev means not programming yourself into a corner. A game is very time consuming to test and its software design changes more rapidly and more completely than any other software project. Therefore, successful game development means being able to try out ideas without turning your project into a mess.

In regular software development this is called finding the correct abstraction. Your ability to do this is limited by the tools you use (engine, language). Think to yourself: if I have to go back and change this part, how annoying will that be? If you have to make mechanical edits in more than two places, you’re doing something wrong.

Godot, while nice, has some limitations that make working with it difficult. Below is a list of conventions I’ve used to try and stay sane.

Reference Nodes via Export

Godot has three ways to reference other nodes within scripts.

@export var mySprite: Sprite2D

func do_something():

$Path/To/Sprite2D.modulate = Color.AQUA # 1

%Sprite2D.modulate = Color.AQUA # 2

mySprite.modulate = Color.AQUA # 3

The first two are effectively hard-coded string keys, introducing a hidden dependency between your scripts and your scene structure. Avoid them. Instead @export them and set the correct node manually in the editor. It’s more work, but if you move any nodes around Godot will update the reference for you.

Separate Data from Visuals

Never have something like this in the same file:

var potion_strength = 5;

# ...

func animate_hover() -> void:

# ...

Always have a class called (for example) PotionInfo that stores all the stats and effects and have a separate class called Potion that is the visual representation of your game element (here, potions).

There are uncountably many reasons to do this. Creating a save file for your game is easier. Duplicating items is more reliable (in Godot it’s especially funky to copy a node). Items that look different (and require different nodes) in various scenarios (potion in hand, potion in inventory, potion as an active status) have a common data backing. Game logic is kept clean while often unruly visual programming is moved elsewhere (and is a generally less impactful place to have bugs). And of course, it’s quicker to test non-interactive code. Do this!

Don’t Create Scenes Too Eagerly

When you’re starting out just keep everything in one scene.

Create a world and a player node and an enemy node all in the same scene. Try and program their relationship. When those are solid and you want multiple copies of something (e.g. multiple enemies), only then right-click and ‘Save Branch as Scene’.

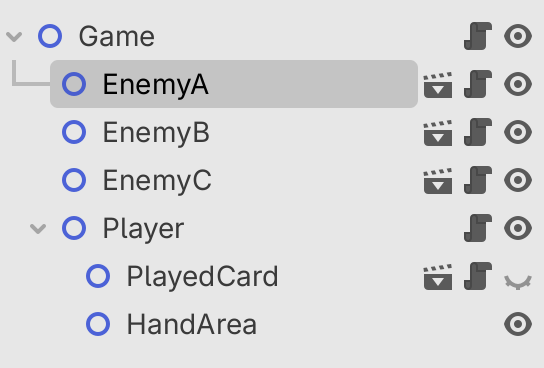

After a while making a card game I ended up with this. Only elements that require multiple instances of themselves are saved as scenes and only when I get to that stage of the project.

Name Your Scripts/Classes

Classes are the only way to have composite data types in GDScript.

You should be naming everything that gets used by something else.

extends Node2D

class_name Card

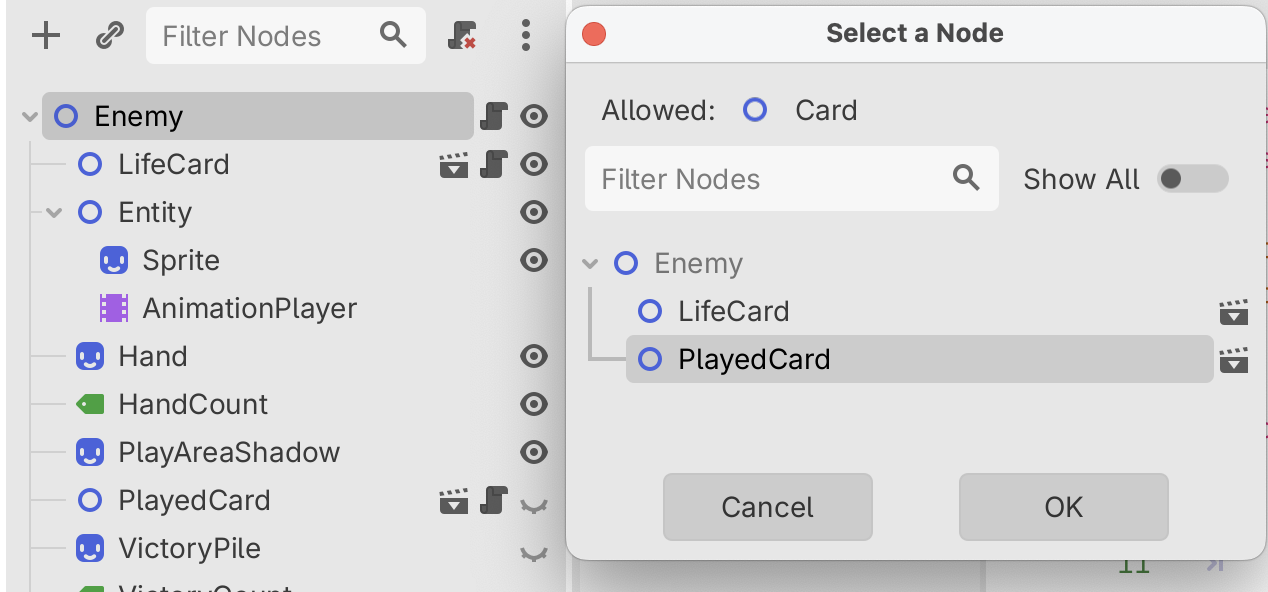

When you do this you also improve your experience finding these nodes with export:

class_name Entity

extends Node2D

@export var played_card: Card

Use Typed Arrays, Dictionaries, Functions

Godot 4.4 (released March 2025) introduced typed dictionaries. You can now do:

var TILE_TO_EFFECT: Dictionary[Vector2i, Effect] = {

Vector2i.ZERO: Fire.new(5),

}

Use type annotations like this for everything.

Your time is too valuable to be chasing down type-level bugs.

Understand GDScript Lacks Type Parameters

For instance, collections in Godot are pretty rudimentary, so this will not work:

@export var enemies: Array[Enemy] # extends Entity

@export var player: Player # extends Entity

var entities: Array[Entity] # a list of the above

func get_turn_order(start: int) -> Array[Entity]:

return range(entities.size()).map(func(i):

return entities[(start + i) % entities.size()]

)

Error: Trying to return an array of type “Array” where expected return type is “Array[Entity]"

This sucks pretty hard and the solution is rather annoying:

@export var enemies: Array[Enemy] # extends Entity

@export var player: Player # extends Entity

var entities: Array[Entity] # a list of the above

func get_turn_order(start: int) -> Array[Entity]:

var out: Array[Entity] = []

var items = range(entities.size()).map(func(i):

return entities[(start + i) % entities.size()]

)

out.assign(items)

return out

Avoid Nested Dictionaries/Arrays

Godot also does not support collection typing that’s more than one level deep, such as a dictionary whose keys are also dictionaries of a certain type. When you find yourself wanting to do this just don’t and make the top-level dictionary terminate at a class instance (that might then contain a dictionary). You’ll also retain your auto-complete in this case.

Use Abstract Classes

Godot 4.5 (released September 2025) introduces abstract classes. Use these to provide a common interface that unites different game elements.

@abstract

class_name Entity

extends Node2D

@abstract func play_turn(round: int) -> Array[Action]

Notice that Godot will now yell at me when I have a class that extends Entity but doesn’t implement play_turn. Amazing! Imagine adding a method to a non-abstract base class and having to remember every inheritor you have to update.

Consider Ditching GDScript

GDScript is improving with every Godot release, but to me the array typing issues alone are enough to warrant a switch. It not only bloats your code with unnecessary lines and memory copies, but it prevents you from making strongly typed and easy-to-use interfaces.

C# is the second-best-supported language Godot has and it’s a bit of a jump in complexity. More expressive types exist in C# (for list processing, etc.), but the language also relies on nulls and exceptions, which makes the gains fairly marginal. Imagine having a null pointer exception in 2026!

A lot of good work is being done in Godot-Rust, and this is a variant I hope becomes mainstream. The downside being extra setup for everyone working on your game (installing the Rust compiler, which outputs platform-specific binaries) and learning a new programming language. Personally I don’t think the language part is a big deal, but it is a shame that there are now extra dependencies other than just ‘Godot’ for your project. That being said, Rust has an exceptional package manager.

Don’t Be Afraid to Throw Everything Away

Sometimes you’ve written yourself into a corner. That’s fine. Instead of chasing down refactoring bugs it might be faster to just start again.